Transforming Connectivity: The Evolution of Iran's Internet Landscape in the Post-Islamic Revolution Era

Introduction

The advent of the Internet in Iran has been shaped by significant political developments. Prior to the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iran had made remarkable progress in various sectors, including substantial investments in the industrial field. However, following the revolution, Iran, along with the entire Middle East, experienced significant transformations. The utilization of computers had already been prevalent in Iran before the revolution, with even the Imperial Iranian Military Industries incorporating them into equipment like Chieftain tanks. The global availability of the World Wide Web, invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1990, brought forth new opportunities for advanced countries connected to the Internet. However, Iran faced the challenges of an eight-year war with its neighbor Iraq, which greatly impacted its technological advancement. The revolution led to the loss of experienced military personnel, with the interim government dismissing 13,000 senior specialist officers. Moreover, there were delays in receiving crucial military equipment from other countries, such as the 200 Harpoon missiles purchased from France, which were diverted to Saudi Arabia. These setbacks deprived both Iran and Iraq of vital resources that could have potentially mitigated the devastating effects of the war and preserved peace in the Middle East. In a controversial move, some individuals within the interim government proposed dissolving the army just 45 days before the war, using the pretext of a "Saving Iran's Great Uprising" or "NEQAB" coup. This resulted in the leading to execution of 45 senior officers from the 92nd Armored Division, effectively handing over the command to inexperienced Iranian teenagers like Mohammad Jahan Ara and Ali Shamkhani. This decision weakened the military's expertise and hindered Iran's technological progress, including its ability to embrace the Internet and modernity.

Background

The development of the Internet in Iran has its roots in the earlier generation of computer networks known as Bitnet, which was widely used worldwide before the advent of the Internet. In 1989, the Institute for Fundamental Sciences (IPM) became the first center in Iran to connect to the BitNet Network, primarily for scientific research collaborations with universities across the globe. However, Bitnet functioned differently from today's Internet, mainly serving as a platform for exchanging electronic letters. Siavash Shahshahani (Former Chairman of IPM), a deputy director of the foundation, recalls that membership in Bitnet came with certain commitments, including a prohibition on using the network for religious propaganda and a requirement to facilitate information exchange between countries. Mohammad Javad Larijani played a significant role in establishing the connection and formalizing agreements. Initially, the center connected to a university in Austria through dial-up connections over telephone lines, but later a Leased Line was established with the University of Vienna, solidifying the connection.

The Internet gradually entered the public domain in Iran, initially serving academic users. The Institute of Fundamental Sciences (IPM) , having paved the way for internet usage, connected to the Internet via the University of Vienna. Other academic institutions such as Isfahan University of Technology (IUT), Sharif University of Technology, Genetics Research Center, and Iranian Seismological Center, followed suit and gained access to the Internet. It wasn't until 1994 that public access to the Internet became available through Neda Computer Institute. This marked an important milestone for Iran's Internet development, coinciding with the registration of the .IR domain, providing Iranian websites with their dedicated addresses.

The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology initially opposed the expansion of the Internet network in Iran, perceiving it as a temporary and trendy phenomenon and tend to mind to develop X.25 protocol. This opposition persisted for some time and slowed down the early growth of the Internet in the country. However, with the utilization of Leased Lines, satellite contracts, and the signing of agreements, progress was made. It took up to three years to establish a connection speed of 128 Kbps through an Italian company. Subsequently, in 1997, the speed was upgraded to 512 Kbps, marking a significant advancement in Iran's Internet infrastructure.

Technical Structure

In the early 2000s, Iran began providing ADSL access, although it was not accessible to all users. The implementation of PCM technology aimed to increase phone penetration, allowing a significant number of telephone subscribers to use their lines for ADSL communication. However, the shared user bandwidth ratio of 1:10 in Iran has impacted the quality of ADSL lines. Additionally, some internet service providers offer wireless internet services like Wi-Max.

Iran's entrance bandwidth is facilitated through optical fiber. Until 2005, the majority of the country's bandwidth relied on the sea cable between Jask County and Fujairah city, leading to vulnerability and disruptions in Iran's internet, particularly in January. By 2005, Iran expanded its internet connectivity to five neighboring countries through Optical fiber, with the exception of Pakistan. Furthermore, Iran expressed its intention to join the Falcon Network, with plans to eventually join the World Fiber Network (Flag) directly within the next fifteen years. In November, the total bandwidth of Iran through these two ports was announced at 1 STM-1, equivalent to 1.2 MB/s, which was later increased to 2 GB/s by the end of the year.

The cost of internet access in Iran varies depending on the connection speed and bandwidth. Internet prices in Iran are considered to be among the highest in the world relative to the speed, quality, and volume of downloads. This is primarily due to the cost associated with the entry of bandwidth into Iran through infrastructure communications companies and its subsequent sale to internet distributor companies.

Transition from Dial-Up to Social Networks

In the initial years following the introduction of internet services by the Neda Computer Institute, dial-up internet was the only option available in the country. However, in 2002-2003, the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology issued PAP licenses to corporate companies, allowing them to provide high-speed internet through ADSL. During this period, high-speed internet services came at a relatively high cost of approximately 500,000 IRRs, which posed a financial burden for many families. Social networks like Facebook gained popularity among users, but they were later filtered, leading to the development of Iranian alternatives through reverse engineering.

Mobile Internet Services

Three mobile companies and Taliya, Irancell, Hamrahe-Avval have been offering mobile internet services. These companies introduced internet access through GPRS or increased data speeds for GSM transformation, along with other internet-based services, including mobile internet banking, for mobile device owners. Currently, most parts of Iran are connected to 4.5G internet.

As per the Communication Regulatory Authority's (CRA) report in 2022, the number of internet users in Iran exceeded 116 million (with 11 million fixed-line and 105 million mobile users). By the end of 2023, the internet penetration rate in Iran was estimated to reach 129%. In terms of fixed internet broadband subscriptions, the majority of users rely on X-DSL technology (77%), followed by TD-LTE (3%), Wi-Fi (3%), and FTTH (2%).

Internet Speed

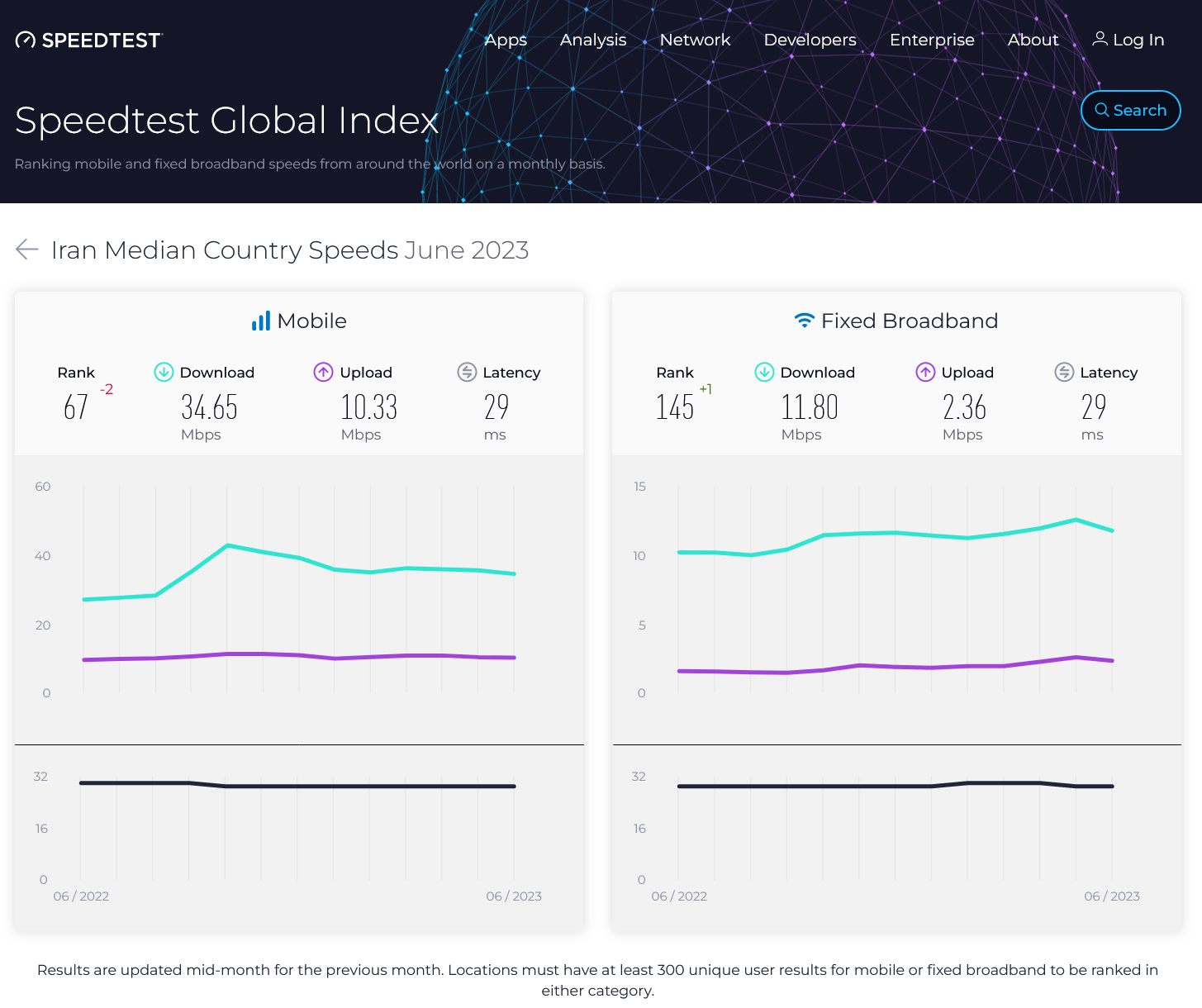

When it comes to internet speed in Iran, there are notable variations between mobile networks and fixed networks. On average, the download speed for mobile internet, including tablets and smartphones, is reported to be 35.68 Mbps, while the upload speed is around 11 Mbps. However, the average download speed for fixed networks is considerably lower at 11.97 Mbps, with an upload rate of only 2.6 Mbps. These statistics are based on the SpeedTest Global Index, which gathers data from millions of individual measurements across 180 countries in April 2023.

Despite advancements in telecommunications, Iran is still lacking a modern 5G network as of 2023. Although large domestic companies like Irancell and the first have launched their initial 5G sites in major cities such as Tehran, Kish, and Mashhad, the public availability of 5G internet remains uncertain. There are ongoing collaborations between Irancell and Ericsson, as well as the first and Nokia, which are expected to contribute to the development and implementation of 5G technology in the country.

According to the SpeedTest Mobile Internet Speed report from May 2023, Iran is ranked 64th globally in terms of mobile internet speed. However, when it comes to fixed internet speed, Iran's ranking is lower at 146th in the world. These rankings provide an indication of the current state of internet speeds in Iran compared to other countries.

Law of computer crimes and filtering

The field of computer crime in Iran is governed by laws that define and address unauthorized and criminal activities related to computer systems, including those conducted over the internet. The foundation of these laws was established in the year 9 during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's presidency. Information Technology Organization of Iran, responsible for overseeing the country's filtering practices, initially relied on foreign software for its operations, starting with US software in 2000 (called Websense). Subsequently, Smart software and WebWasher software was utilized until November 2006. While these tools did not control email and chat environments, they incorporated web robotic filtering capabilities to automatically and intelligently search for and classify blacklisted content based on defined criteria. To enhance their capabilities, a tool called Delta Global was acquired and utilized. However, due to the limitations and costs associated with foreign tools, there was a shift towards domestic production. Several companies obtained approval from the Information Technology and Judiciary Company to develop tools that would cover the delivery route and could be used by internet service providers. After addressing initial shortcomings, the Carrier Class took over the responsibility of delivering refined content. The success of this endeavor prompted reconsideration of foreign tenders, leading to the assignment of this responsibility to the Infrastructure Communications Company following the enactment of the Computer Crime Act in 2009.

With the adoption of the Law of Computer Criminal Act and the Criminal Computer Criminal Content Identification Group in 2009, a designated group was entrusted with the responsibility of determining and addressing specific types of criminal content. This group operates in accordance with Chapter 5 of the Computer Crime Act, as well as the laws of the Islamic Penal Code, the Press Act, and the resolutions of the Supreme National Security Council. The categories of criminal content include many items, but are not just limited to:

Content that violates chastity and public ethics.

Content that undermines Islamic sanctuaries.

Content that threatens security and public peace.

Content that targets the government, public authorities, and institutions.

Content used in the commission of computer crimes.

Content that promotes or incites other forms of criminal activity.

Criminal content related to audiovisual affairs and spirituality.

Criminal content pertaining to the Islamic Consultative Assembly.

Criminal content associated with presidential elections.

Iran's Cyber Police (FATA):

The FATA Police, an integral part of the Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a specialized unit dedicated to combating a wide range of cyber-crimes. With a focus on maintaining cybersecurity and safeguarding the public from online threats, the FATA Police plays a vital role in addressing issues such as phishing, internet fraud, hacking, organized computer crimes, explicit content distribution, and privacy violations. This unit operates with the aim of ensuring a safe digital environment and protecting individuals from the negative impacts of cyber activities.

The implementation of internet filtering in Iran began in 2001 with the issuance of the "General Policies of Computer Information Networks" by the supreme leader. A year later, a committee comprising representatives from the Ministry of Intelligence, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, and the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) was formed to oversee the filtering process. Initially, the committee provided a list of 111,000 banned sites and instructed internet service providers to block access to them.

Additionally, the judiciary also ordered the filtering of several websites during that year.

Internet based services

Internet-based services in Iran rely on the “Shaparak.ir” gateway for online payments, which can only be accessed with an Iranian IP address. To conduct transactions, users need to provide their bank card information, CVV2, and receive a randomly generated second password sent to their mobile number. Additionally, obtaining licenses from “eNamad” and “Samandehi” systems is crucial to ensure the authenticity and validity of websites used for banking transactions. This allows users to have recourse in legal forums and seek resolution or refunds in case of any issues or disputes.

Iran National Information Network (NIN) or National Intranet

The concept of the National Information Network (NIN) or National Intranet was first introduced in 2005, aiming to establish an internal network to gain more control over internet users and enable the government to disconnect from the international internet when deemed necessary. Over time, this project has been fully developed and implemented, allowing the government to cut off the internet during protests and filter access to international websites, while maintaining access to Iranian government sites.

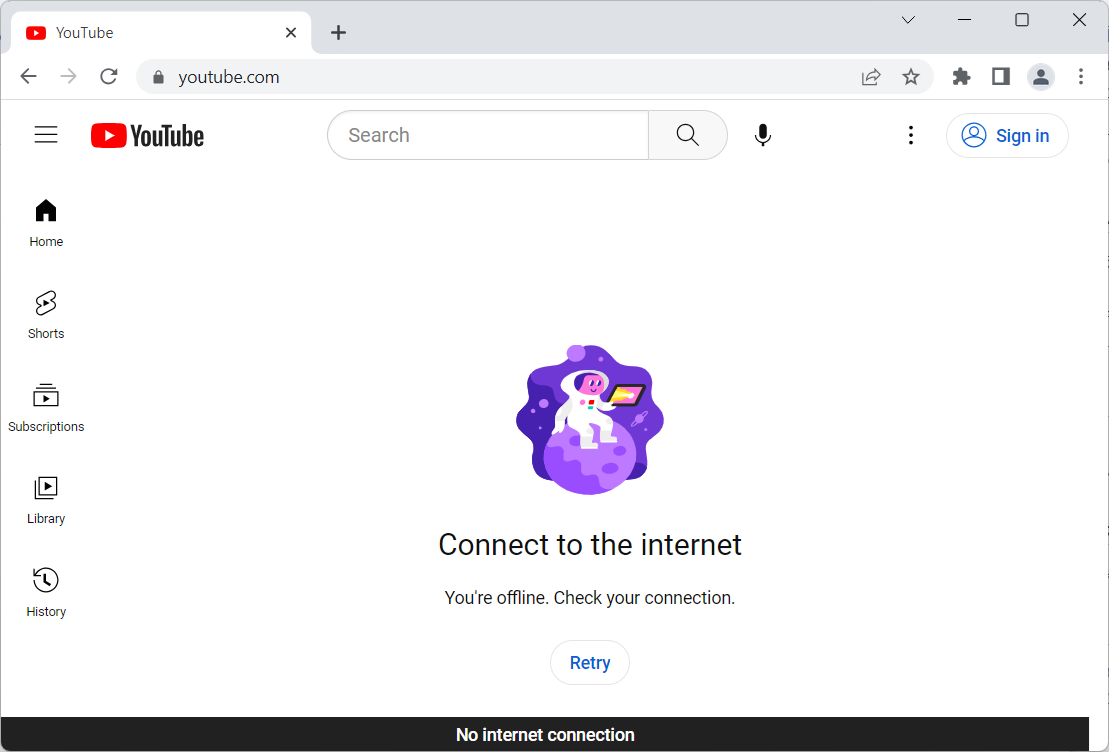

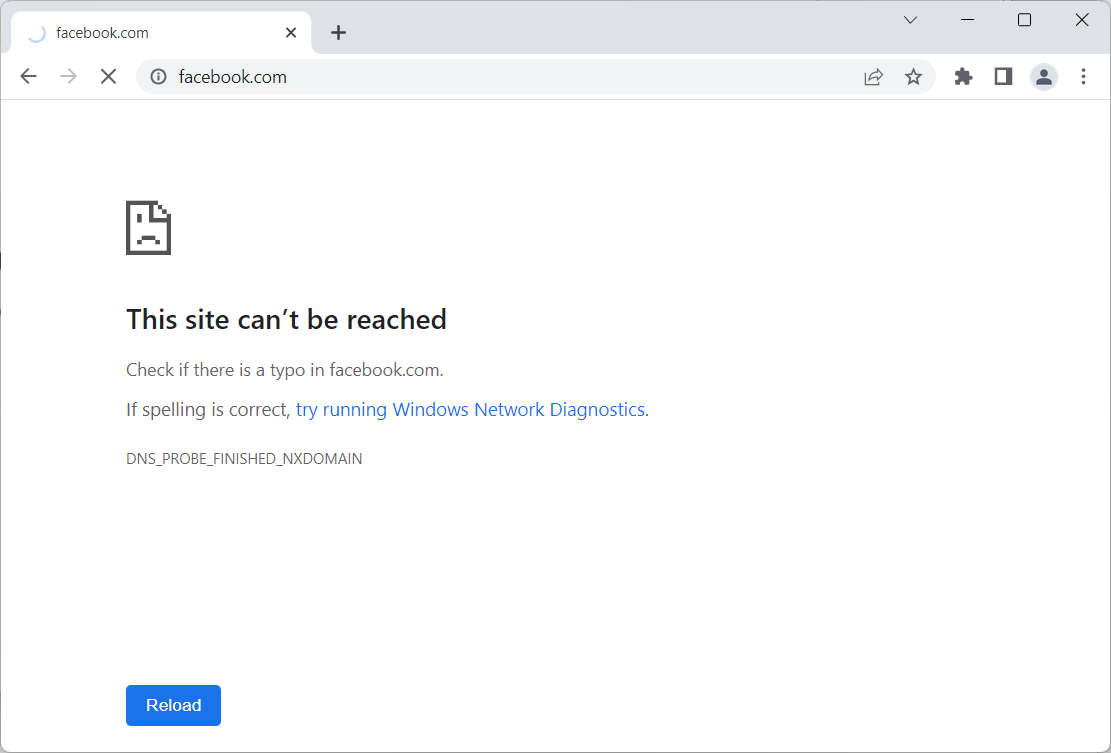

In Iran, there are extensive efforts to control the flow of information, including the filtering of various social networks and foreign messaging apps. A range of platforms such as Telegram, WhatsApp, Signal, WeChat, Facebook Messenger, Viber, Line, Snapchat, ICQ, Paltalk, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, YouTube, TikTok, Tumblr, Quora, Flickr, Meetup, Badoo, VK, and more are among the filtered sites. However, it is important to note that the mere usage of these services is not considered a crime, unless it involves the publication of content that insults the sanctities of the Islamic Republic of Iran, such as images without Hijab.

To address the limitations imposed by such restrictions, many Iranian-developed messaging apps have emerged through reverse engineering of Telegram. These apps are now mandatory in various government agencies. Iranian users are well aware of the motivations behind these measures, as they pertain to control over mobile phones and access to contact information.

A project called protection of Cyberspace

Iran's approach to internet filtering is often compared to the Chinese system, as the government seeks to exert comprehensive control over users' activities. For instance, Safe Search ON, a search engine feature that cannot be disabled without using a VPN, poses challenges for Iranian users as major companies like Google and Microsoft have not provided a solution. The government has actively deactivated most VPN protocols, and since using VPNs is considered illegal, individuals involved in their buying or selling can face legal consequences. However, certain protocols like V2ray, similar to China's VPN system, continue to function effectively in Iran.

In addition to internet censorship, internet cafes in Iran are required to authenticate users and keep records of national ID cards, logs of day and time, IP addresses, and a list of visited sites for at least six months. Registering .IR internet domains also entails providing comprehensive personal information, including the national code, phone number, address, and postal code. These measures contribute to the government's efforts to monitor online activities and establish tighter control over internet access.

Iran Cyber army, a political usage of computer science experienced people as tool

In recent years, it has forced people with top computer experience into a bad game where you either have to work for us against our enemies, or you will be sentenced to years in prison, or your family will be threatened. The suspicious death of former Iranian Cyber Army member Mohammad Hossein Tajik raises concerns about the extent of control and coercion within this realm. Assumptions based on, online forums such as Ashiyane and their affiliated personnel operate directly under the supervision of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Iran's cyber army.

If we want to name a few of the activities of this mercenary group, the following can be mentioned:

· Hacking and infiltrating about 500 American government websites.

· Hacking the NASA website.

· Hacking a large number of sites that used the word "Gulf" instead of "Persian Gulf".

· Hacking several Danish websites (a reaction about of the caricature of the Islam Prophet)

· Attacking and infiltrating several Israeli websites.

· Hacking some of the most important internal websites related to government institutions due to keeping their news platform silent against possible risks against government.

· Hacking into some of the most important sites in Saudi Arabia and Wahhabi-related institutions.

Additionally, the Ministry of Information (VAJA) and IRGC organizes a big group of individuals tasked with manipulating hashtags, posting extensive comments, and employing macro-level strategies to influence internet-related objectives, such as manipulating online voting processes, to show fake result of Iranian thinking and decision. They commonly called to as "Cyberi" force. Although unofficial statistics are much higher, IRGC officials have officially stated that 144 IRGC cyber battalions operate in just in Tehran.

Meanwhile, in recent years, Iranian websites, as well as government, military, and nuclear institutions, have faced numerous cyber-attacks and instances of cyberbullying aimed at undermining Iran's nuclear program. Malware such as Flame, Stuxnet, and Stars, which are known to have significant impacts, have been deployed on Iranian computer systems. As internet access in Iran has increased, so has the prevalence of internet-related crimes. To address these issues, the Iranian police established a cyber-crime division (called FATA), acknowledging the need for a dedicated space to combat such threats.

However, it is essential to note that there have been instances of misconduct within FATA division. In November 2012, a tragic incident occurred when a worker and a 35 years old blogger, who had been arrested by FATA Police, died during interrogation. This incident led to the dismissal of the Tehran FATA Police Chief in response to the violation. It is crucial to recognize that while financial crimes are prevalent in Iran's cyberspace, other forms of cyber-crime also exist.

Honey-trap

There are speculations that in Iran, the IRGC try to organize online prostitution women, make a sex-traps to identify protesters or identify the possible location of subsequent protests.

Buying webmasters of music and movie download sites

The closure and destruction of many old Persian Internet forums by the Iranian government has limited free access to information. Due to the lack of copyright enforcement in Iran, the government has colluded and paid money to the owners of movie and music download sites, resulting in restrictions on Iranian users' access to foreign singers and Persian-language artists based in Los-Angeles, ultimately undermining their audience.

In recent years, particularly in 2009, 2019, and 2022, there has been significant popular dissent (protest) against the government in Iran, leading to numerous imprisonments and casualties. In response to the recent protests following the tragic death of “Mahsa Amini” by the Guidance Patrol, the government has announced the procurement of 10,000 CCTVs from China and the use of artificial intelligence to monitor individuals without proper headscarves or deemed to be dressed inappropriately. Offenders will be notified via SMS and fined accordingly. The government has already established the infrastructure to capture bio-metric photos of individuals' faces through changes in the national ID card system, making face recognition a relatively straightforward task. Presently, women who are caught driving without a hijab receive an SMS notification, resulting in their vehicles being impounded and facing fines.

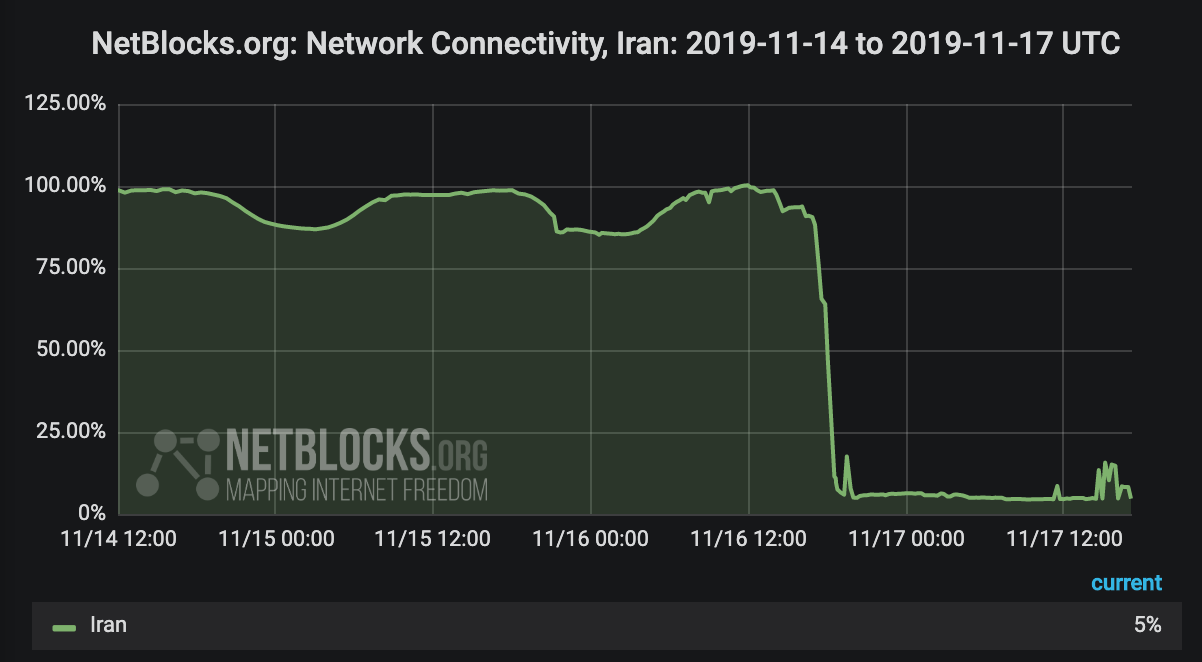

Deceptive Practices: Governments' Fabricated Data and Internet Blockage

In instances of Internet blockage, Iran government have been known to employ deceptive tactics, such as sending fabricated data to organizations like NetBlocks.org, in an attempt to maintain the illusion that the Internet is still accessible within the country. This deliberate dissemination of false information serves as a blatant manipulation of the truth, designed to mask the true extent of censorship and control exerted by government. It is a concerning strategy that undermines transparency and inhibits the free flow of information, ultimately depriving citizens of their fundamental rights to access unbiased and unrestricted communication channels. The repercussions of such deceitful practices can have far-reaching consequences, further highlighting the importance of safeguarding online freedom and combating such deceptive tactics.

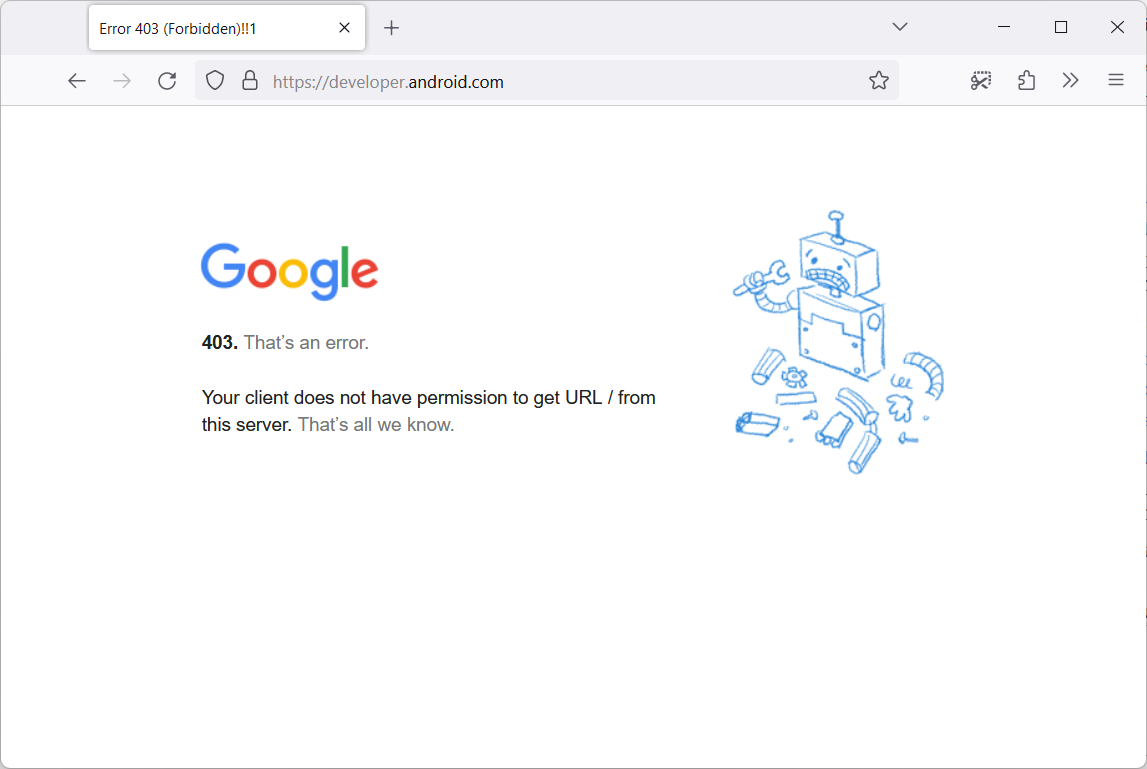

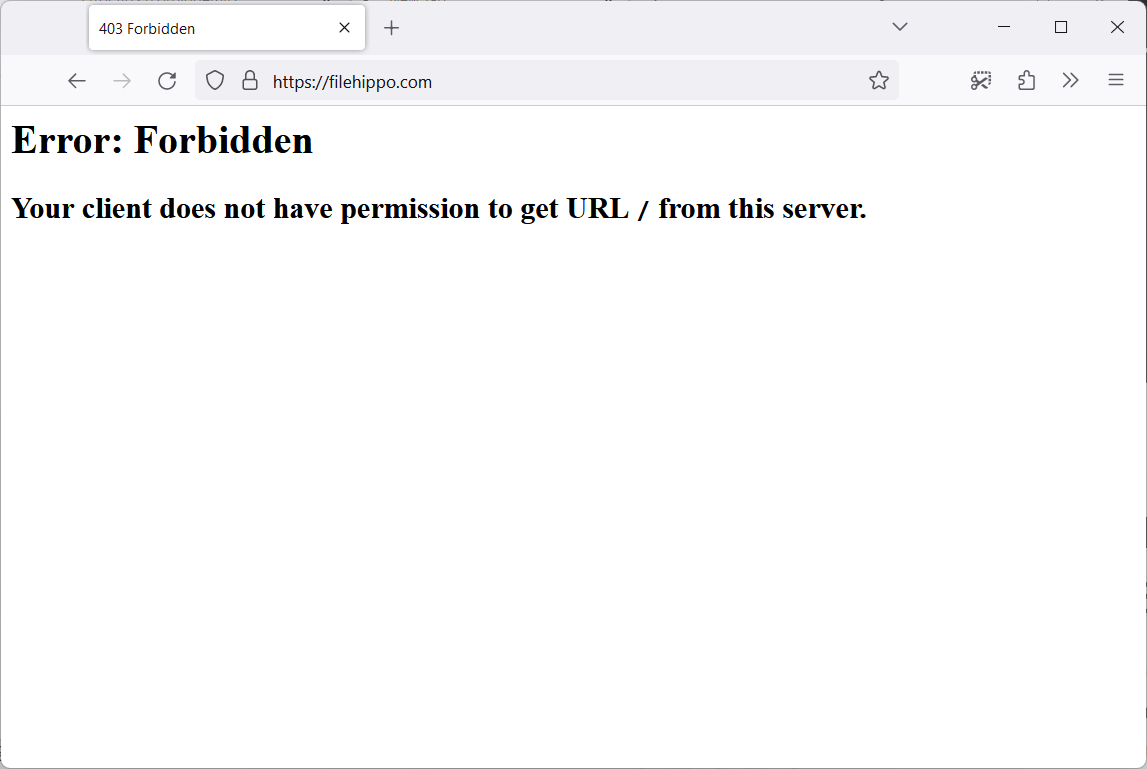

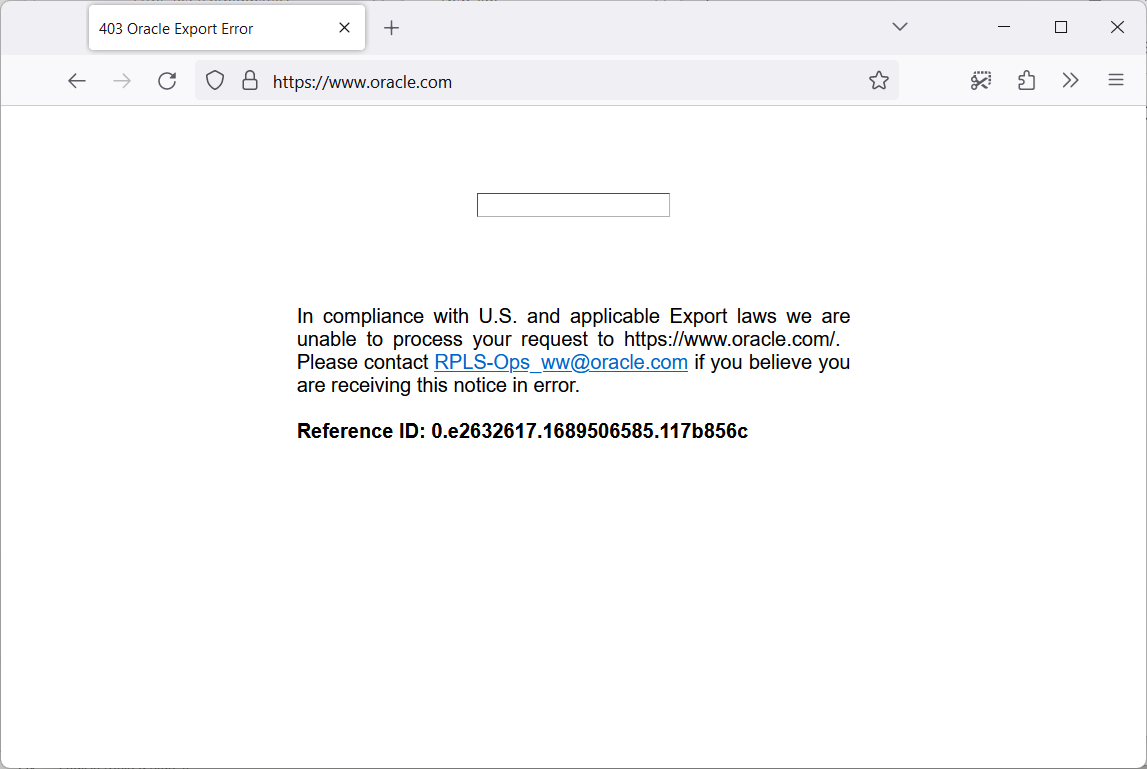

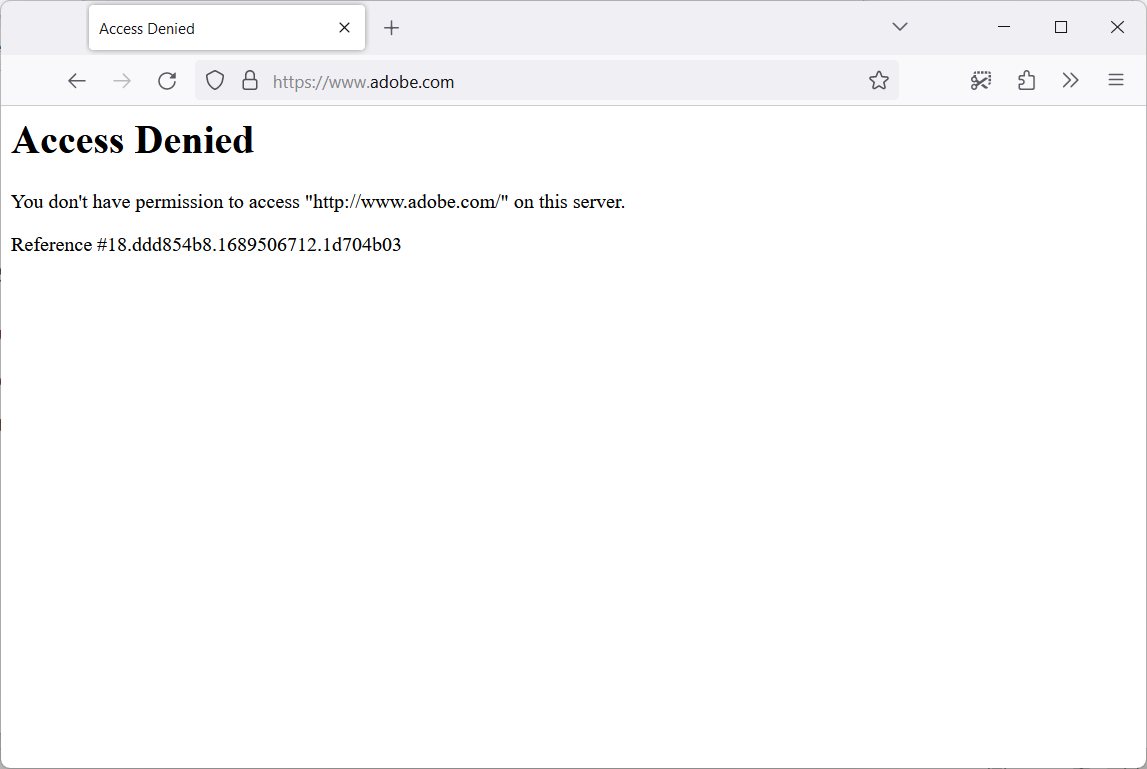

The Hidden Woes of Iran's Internet Experience: An Unveiling of Limitations and Restrictions

The Iranian internet landscape is marked by the painful reality of international sanctions that restrict access for Iranian users. As a result, many websites are compelled to limit their services to comply with these sanctions, exacerbating the restrictions faced by Iranian internet users. These limitations often go beyond the scope of the imposed sanctions, prompting users to seek alternative solutions such as anti-filter software to bypass these restrictions. Surprisingly, evidence indicates that the IRGC itself is involved in selling VPNs to Iranian users through intermediaries, effectively filtering and profiting from the same censorship it enforces. Moreover, high-ranking officials who have held positions within the Iranian government for nearly 45 years, despite being subjected to international sanctions, possess intricate knowledge of evading these measures and safeguarding their illicit assets in private banks. The ramifications of these restrictions are profound: Iranian individuals find themselves without access to international banking platforms like PayPal, unable to engage in global transactions, and social networks remain blocked and filtered. They can’t work internationally as an Iranian. Consequently, the voices of protesters are stifled, preventing their grievances from reaching the ears of the world. These are the immense challenges and pain that Iranian youth grapple with on a daily basis, as their fundamental rights are violated by the Iranian government.

Conclusion

Amidst the numerous challenges and setbacks faced by Iran in various aspects, it is worth mentioning the insightful words of Muhammed Anwar al-Sadat, an esteemed Egyptian politician and military figure. Upon hearing about the passing of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, he retreated to his room and expressed, "You died at 9:17 am, and Iran at 25 o'clock."

In a subsequent press interview, he eloquently stated, "Today, we bid farewell to a man who relentlessly pursued peace. With his departure, the Middle East lost its beacon of tranquility and prosperity. Though he may have passed this morning, Iran's progress halt at 25 o'clock." (It is reminiscent of the French proverb, which emphasizes that a day comprises 24 hours, and 25 o'clock symbolizes the hour of passing.)